From just 34 riders racing out of a small town in America’s Midwest to the biggest and most revered gravel race in the world.

Welcome to Unbound

Words JOE LAVERICK Photography LIFE TIME

Emporia, Kansas: small town in the Midwest, population 23,844. Pre-2006: self-proclaimed Disc Golf Capital of the World as host of the Disc Golf Open.

Post-2006: widely acknowledged as Home to the Spirit of Gravel thanks to hosting Unbound Gravel – 4,000 riders, hundreds of miles of dirt, self-supported.

Unbound has been compared to the Super Bowl or the Tour de France and is unofficially the biggest race on the gravel calendar, the race everybody is desperate to win.

So although the majority of participants are in it for the challenge, to line up in Emporia is to line up next to the biggest names on the circuit, including many who sound familiar.

Ex-Sky rider Ian Boswell won Unbound 200 in 2021; last year EF Education’s Lachlan Morton was third in the same event while Canyon-Sram’s Tiffany Cromwell won the women’s Unbound 100.

Cycling is often credited with being one of the most accessible sports in the world. You can’t kick a footy around the MCG, but you can ride up Alpe d’Huez any day of the week. Unbound pushes it all a step further.

It takes all kinds

The marquee option here is Unbound 200, a 200-mile course which first took place under the banner ‘Dirty Kanza’ in 2006, attracting just 34 dedicated riders.

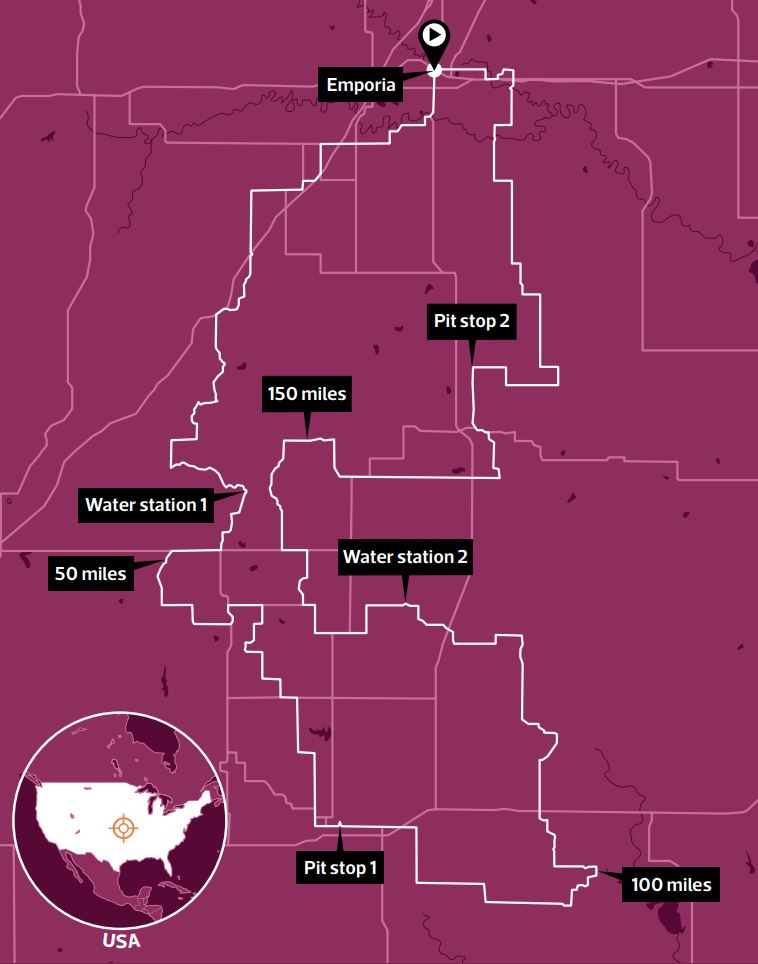

These days Unbound has six distances: 25, 50, 100, 200, 350 XL and Unbound Junior, open to kids from 12 to 18 years old. Each event’s length is as its name implies, in miles (this is America after all), and each sets out into the Flint Hills of Kansas.

Back in 2006 you were likely to see Unbound ridden on cyclocross or mountain bikes, but todaymost riders, including me, are on gravel bikes. Like chickens and eggs it’s impossible to say if Unbound fuelled gravel bikes or vice versa, but it hardly matters.

The beauty of gravel is that it doesn’t require dissecting – not only does it lack the tradition of road cycling, it actively eschews it. There are also no cars, which is a huge draw. All of this has drawn me from a career racing on the road and into gravel.

This is my first year racing as a ‘privateer’ – a model where riders organise their own sponsors and choose which disciplines and races to compete in.

I looked to do a block of races in North America but wanted to avoid Unbound this year, saving the epic 200- mile race for another season, but then came peer pressure from friends and sponsors, and by some miracle, I got in via the waitlist.

That’s another thing – 4,000 competitors there may be, but the application numbers are significantly higher.

Kindness of strangers

Emporia is located some hundred miles southwest of the airport and there is a distinct lack of public transport between the two, so I put a shout-out on the Unbound Facebook page to see if anybody could help with transport.

I’m in luck. Kansas resident Jim Markel, an Unbound race volunteer whose duties include helping foreigners like me to and from the airport, drops me in town and I offer to pay for gas. He refuses – apparently I’m a guest of Kansas.

The sound of freehubs echoes loudly around the high street; nervous chatter about tyres and weather dominates the conversation in cafes and bars. But as the day progresses, the air becomes heavier, at first metaphorically but soon literally.

It’s dinner and I’m about to cram down a metric ton of rice when the heavens open. A healthy number of expletives are thrown around the table as we discuss the impact this will have on the course.

Whether your goal is to win in a time of less than 10 hours or simply finish within 20, the questions remain the same.

What tyres shall I use? What pressure? What gearing? What nutrition? What spares? Then throw in a pre-race storm.

Right up until the 6am roll-out time, the list turns over and over in my head, only temporarily silenced by sleep.

Blinking peanuts

The Star-Spangled Banner has just finished. Anticipation and trepidation fill Emporia’s High Street. The countdown reaches zero and we pull away. This year, organisers chose to split up the amateur and pro categories for the first time in view of safety, and it seems to be working.

I’m in the pro category, I’m nervous, but the start is surprisingly calm. We turn right, off the tarmac and onto the gravel, and there’s a small fight for position but nothing major. Nobody wants to blink first in a 200-mile race.

Without warning I get heavily pushed from my right, putting me out of position going into the first steep climb. The climb is hard and taken fast, but it’s expected that a main group of riders will stay together for the first four or so hours so there’s no need to do anything stupid.

We descend, take a right-hand turn as my computer ticks over to 15km, and it’s a mud bath. Last night’s rain has turned a fast-flowing, hard-packed trail into a bog, but being out of position plays in my favour as I’m able to choose my own line.

I sail past countless riders stuck in the mud. Then I come to a stop myself, dismount and start running. The infamous ‘peanut butter’ mud is just impossible to ride, clogging not just tyres but drivetrains and frames.

The rugged nature of Unbound means making the right decisions can completely change the outcome of your day, so with that in mind I stop to clear the mud from my frame and groupset with a highly specialised tool I’ve packed.

I’ve lost a little time but it’ll pay dividends, I think, as I return the wooden paint stick to my back pocket. I hop back on and try to ride but it’s onlya few hundred metres before my bike clogs up again, and soon Unbound has gone from gravel grinder to hike-a-bike.

Even pushing my bike through the mud is causing it to clog up; soon my trusty stick is so muddy it needs its own stick, and I resort to using my hands.

‘I wish I’d been good enough to stay on the road,’ I exclaim, half-joking, half-serious, which gets a few laughs from the riders around me.

Over before it began

There might be some 300km to go but my race is effectively over – the mud incident has meant a group of ten is already ten or so minutes ahead.

I stop in a small creek to wash the mud from my bike, cursing at how far I’ve come and how much money I’ve spent to get here, only for my race to end prematurely. Only that’s not quite true.

If you have any issues in a pro road race it means an early shower, but in a race like this, with no in-race support, you just have to keep going. And the result is something of an epiphany.

A few hours pass of me feeling sorry for myself, but then I see the light, Unbound – that spirit of gravel – working its magic on me through a combination of scenery and camaraderie.

I link up with fellow Ribble-sponsored rider Metheven Bond, then we bump into women’s Gravel National Champion Danni Shrobshee. We form an alliance. Better for a few to ride together than everyone be stuck in no man’s land. I feel the strongest I’ve felt all day.

Being so far back means a lot of carrots out in front of me to catch, and there’s plenty of space for them. The Flint Hills of Kansas are vast, the sort of place the phrase ‘God’s country’ was invented for. We stop at a water oasis, still hours away from the second and final pit stop.

We fill our bottles but are desperate for sugar. A large cooler sits to the side with some locals selling a whole array of drinks. With no cash my head drops and my dreams of something cold and sugary disappear, until a can is thrust into my hand with a smile and a wave.

Whoever you are, thank you. We continue to make headway on the next sector. The long, straight Kansas roads coupled with the aero ‘puppy paws’ position (UCI rules have no place here) means we make good time. Then, just before the final pit stop, I bid my group farewell.

Nature calls and my team’s support tent is just up ahead. But I’m happy enough to lose my group, as there’s only 30km to go.

Famous last words

Out of nowhere the skies turn black, the temperature plummets and soon the rain’s so heavy it physically hurts my face. But I can’t stop, there’s a toilet to get to. I skid into our support tent and get pointed to the portaloo.

Some happy minutes later I emerge with a catwalk strut, but the rain is still flowing so I opt to wait it out. I laugh and joke with the locals helping us out, and question how life has got me to this small gazebo in the middle of Kansas.

I eventually cross the line some two hours down on my original plan but with a huge smile.

It’s telling that had I stuck to my pacing I’d have won Unbound outright, the course conditions meaning the winners were 45 minutes slower than the previous year, but I have few regrets.

This way, I really feel I’ve experienced everything Unbound can offer. Now to find a jet wash.

The aftermath

It’s long past dark and we’re sitting on an Emporia kerbside with a beer in one hand, burrito in the other. Participants slowly trickle in, each one met by a cheer from the crowd.

It’s both professional and grassroots at the same time, the only bike race I’ve ever seen with an atmosphere like this.

Every rider has a hundred different stories about their day, from the mud to mechanicals to getting heat-stroke one minute and getting beaten by hail-like rain the next.

You enter via a lottery, there’s the potential for hellish mud and biblical rain, but ultimately it’s all worth it to be part of the infectious spirit that comes when thousands of people travel somewhere to do what they love.

Joe Laverick is a freelance racer and writer who’s going to need a bigger stick

The details

It’s a chance to be in the same race as the pros

What Unbound

Where Emporia, Kansas, United States

How far 25, 50, 100, 200 and 350-mile options (50 and 100-mile races include junior options)

Next one 31st May-1st June 2024

Price TBA [expect to pay $35-$270 depending on distance]

More info unboundgravel.com

Who you know

An insider’s guide to the Unbound galaxy

There are two official pit stops at Unbound, as well as two other water stations.

For the top pros, the pit stops are Formula 1-style. A team of staff gets you turned around within minutes, with wheel guns deployed for fast changes and pressure washers brought out to clean off the mud. The only rule is you have to start and finish on the same frame.

Those of us racing without teams and budgets rely on the support of locals. I was put in touch with a small group of volunteers who link up with the local Irish bar and, for a $100 donation to the local MTB programme, the Mulready’s Pub crew gave me pro-style support.

So just like a big-name pro, I could pull into a pit stop, hop off my bike and straightaway there would be a small group from Mulready’s cleaning my drivetrain and fixing an issue with my bottle cage.

Shawn and Lynnette are just two of the people who made all of this possible, so I’d like to thank them for making my Unbound experience what it was, and for taking over where my beloved wooden stick left off.